The American Presidency is a fascinating institution and one that has grown and changed over its two-and-a-quarter centuries. Like any complex social phenomenon, it has both manifest and latent functions. We all learn in school, for example, that the president is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, as specified in the Constitution, but did you also know he is the chief priest of the state religion?

Don’t believe there is one? Go visit the National Archives sometime and walk into the rotunda housing the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Note the architecture and the hushed voices, like the passing of the host before the altar at communion. On the walls you’ll see the pictures of the holy saints of the American faith — Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln.

And the president is the head, called upon to deliver a sermon to Congress once a year (and to the people regularly), expected to console the nation in times of disaster, and to eulogize the passing of any notable citizen. This, incidentally, is why it is so easy for people to accept the “separation” of church and state in the modern era. The one simply ate the other.

But despite his military and priestly roles, the president is primarily a political figure. He — and I am using the masculine pronoun simply because the office has been one big sausage fest to date — is the chief executive of the government and the second arbiter of the national agenda (the first being the news media).

Trends in the presidency, then, are evidence of larger political trends in the country, and indeed they often track with the increasingly shared sociopolitical development of the English-speaking world at large. This is not exact of course, but there is a reason why the conservative Reagan/Thatcher regimes rose together and were followed, with or without interruption, by the “centrists” Clinton and Blair.

This being a presidential election year, I thought it would be worth it to review how we got where we are.

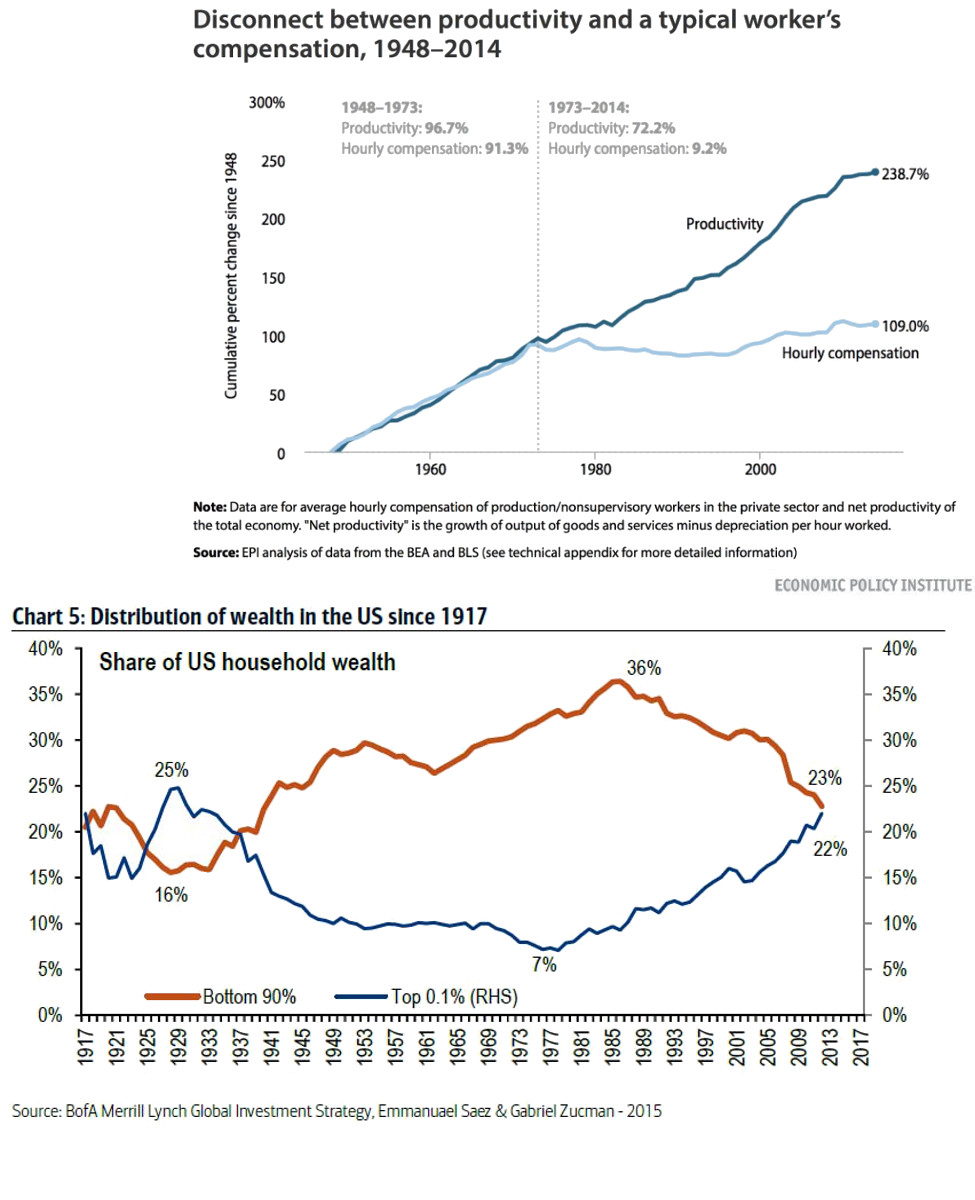

The Pew Research Center issued a report not too long ago that suggested income inequality — to say nothing of wealth, which is different — has reached levels not seen since the 1920s, the end of the aristocratic era, thus erasing the middle class gains of the 20th century. And that’s where our story begins, in the 1920s.

At the time, most of the western world did not live under democratic capitalism. It lived under an aging aristocratic capitalism, which imploded in 1929. This came after a decade of post-war prosperity — the Roaring 20s — where the United States was manufacturer to Europe, whose infrastructure at home had been devastated by WWI and whose colonies overseas were becoming increasingly costly and difficult to manage.

To say the Great Depression was a shock is an understatement. Reading the op ed pieces in the years leading up to it, you would have expected the party to go on forever. (It was the same in the 90s.) But what got people most was how their money just vanished. Poof! It didn’t seem possible. They had earned it. It had existed. No one stole it. So where did it go?

Remember, at this time there was no such thing as government-insured deposits. (The FDIC wasn’t created until 1933.) Individual deposits were, of course, taken by the banks and invested, loaned at interest to someone else. In other words, banks use your money to make more money for themselves.

Then they want a bailout — taken from taxes on the people — when it all falls apart. But I digress.

After 1929, people saw their cash deposits disappear along with their hopes, and they inaugurated a shift, or realignment as the political scientists say, in American politics. The Republicans — once the party of Lincoln, the Great Emancipator — sided with business on the theory that when businesses were happy, everyone was happy. Democrats, led by a wealthy aristocrat (of all people), Franklin Roosevelt, gave the country a New Deal.

From this point, and for roughly the next forty years, American politics staggered left. We were not a leftist country. We have never been a leftist country. But the national agenda was more progressive than not — from the FDIC to Social Security to the integration of the armed forces to Medicare to the Voting and Civil Rights Acts, and so on. And in foreign policy, the establishment of the United Nations (where Wilson’s League of Nations had failed), the Marshall Plan, etc.

These kinds of things — a basic social safety net, government agencies empowered to protect the public commons, regulation of finance, greater protection of minorities, and so on — had never, ever existed. Ever. In the grand sweep of history, the progressive gains of the 20th century are the exception, and they were only made possible by a political consensus born of the unprecedented suffering of the Great Depression and the unprecedented slaughter of two world wars, which killed far more people than any conflict ever in the history of our species.

The office of the presidency mirrored this shift. Roosevelt and Truman were Democrats, as were Kennedy and Johnson. And Eisenhower, the lone Republican, was completely unlike his contemporary colleagues. He believed in a 90% marginal corporate tax rate, created a huge national interstate highway system, and sent the National Guard to Little Rock to forcibly uphold racial integration of schools. (The former Supreme Commander of the Allies even coined the term “military-industrial complex” and warned people about it in his farewell speech.)

So what happened? Well, success for one. The New Deal was never intended to make America socialist, and it accomplished what it set out to do. Banks were reformed. A basic social safety net was created. Overt racism was, at least by the letter of the law, illegal. Government agencies like HUD and the EPA were created to keep an eye on things. The nation was prosperous.

By the end of the 60s, the exceptional liberal consensus that had governed the country for 40 years fell apart as a diverse array of interests sought to define the next agenda. The result was the 1968 Democratic National Convention, famously a complete chaos where no one could agree on anything.

The 1970s saw a transition. The prosperity that underwrote the creation of large government entitlement programs vanished as our natural resources — cheap and ample for two hundred years — dwindled at home and the rest of the world finally emerged from the long shadow of WWII. Japanese cars eroded the long American dominance of the global auto industry. OPEC shocked the world with price controls. And a new word, “stagflation” — the seemingly paradoxical simultaneous occurrence of both inflation and economic stagnation — hit the cultural lexicon.

Enter Ronald Reagan, who promised everyone that it was “morning again in America” and then proceeded to deficit-spend his way to the destruction of the Soviet Union. Carter, the lone liberal of this era, only won because of Watergate (a stumble on the rightward lurch) and was swept away as soon as that fell from the national consciousness.

I say lone liberal because Clinton — the first Boomer president — was not really a liberal Democrat. He was the champion of the so-called third way, and his major accomplishments in office were on traditionally Republican, center-right issues rather than progressive ones: business-friendly treaties like NAFTA, kicking people off welfare, balancing the budget, the repeal of the Glass-Steagall provision of the 1933 Banking Act, etc.

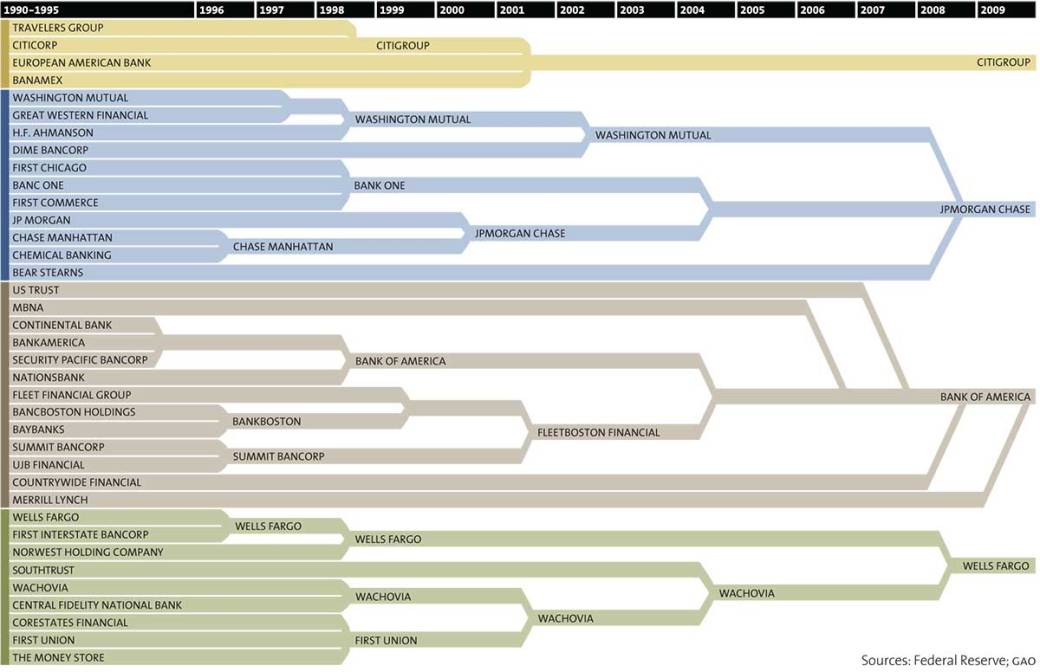

The latter, in particular, is important. Passed after the 1929 crash, it forbade retail banks from engaging in risky investments — a fair requirement given that, in return, the government assumed all their liability by insuring retail deposits through the FDIC! While it is a legitimate question whether the provision would have prevented the financial crisis, there is no question that Clinton’s response to the changing face of modern finance was to embrace further deregulation, and that after Clinton’s 1999 repeal, the major banks entered a period of massive and unprecedented consolidation — measured in terms of net worth — whereupon barely a decade passed before they created another global economic crisis.

It is significant that the Democratic Boomers — Obama and the Clintons — have all responded to the collapse of liberalism in 1968 by moving right relative to their parents’ generation. Of course, twenty years ago, when the Soviet empire expired, the internet burst to life, and the government held a surplus, a third way didn’t seem like a bad idea.

But it’s been a helluva ride since then: Enron, WorldCom, 9/11, two wars, Guantanamo, Abu Graib, Hurricane Katrina, the housing collapse, the auto company bailouts, Justin Bieber, Edward Snowden, Donald Trump, the alt-right, and the death of privacy, just to name a few. And as the Pew study sows, 40 years of right-leaning government, along with a host of global factors outside anyone’s control, has erased the middle class gains of the 20th century. As soon as supply-side policy hit right about 1980, income inequality started growing as those at the very top pocketed productivity gains — what is called skimming the cream — which in the earlier era had been shared at all levels of the firm.

Note that this trend continues unchecked through the twenty-four year period 1993 to 2016, all but eight of which saw a Democrat in the White House:

The choice before us now is: more of the same or try something different. I can’t see why any rational person would think another decade of supply-side tinkering will lead anywhere but further down the road of greater gains for fewer people, which is not just an argument against Republican policies, but centrist Democrat ones as well.

Of course, that raises the question: After a tumultuous opening to the new millennium, are we now poised for another political realignment? Certainly the Sanders phenomenon and the probable nomination of Donald Trump indicates the American people are willing to consider new and “alternative” forms of government.

Sadly, the answer is “probably not.” The political class, which encompasses both sides of the aisle, have no grand vision other than opposition of each other. I suspect we will need to witness another Great Depression, or another global war, before they’re motivated to take lasting steps against demagoguery. Such are the limitations of democracy.

But let’s hope I’m wrong.

Reblogged this on Serum and commented:

I posted this on March 3rd of this year. It is still relevant to how we got here.

#Trump #Election #Election2016 #PresidentTrump

LikeLike

Pingback: Politics is a sport – Serum